A Journey to 16th Century Venice

The Shaping of the Daf: Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz of the House of Baruch and his Remarkable Impact on the Talmudic Daf

Whether you call it ‘the Daf’, ‘the blatt’, or the Talmudic folio, the ancient yet ever so relevant pages of the Talmud Bavli are the cornerstone of Jewish life. With the establishment of the Daf ha-Yomi by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in 1923, study of the Daf has seen unprecedented growth. With technological advancements of the 21st century, global Daf networks have been established and are growing at remarkable rates beyond the imagination of the movement’s founder. Although the Daf is so much a part of our daily lives, it’s worth noting that in the broader picture of Jewish history the Daf is a relatively new invention.

Did Rashi and the Rambam study Gemara from the same Daf we use today? What did the study of the Talmud look like in the prominent Talmudic academies of the Ramban and the Rashba?

In this post, we will journey to northern Italy to encounter the creators of the Daf Gemara.

Life before the Daf: The Era of Talmudic Manuscripts (Kisvei Yad)

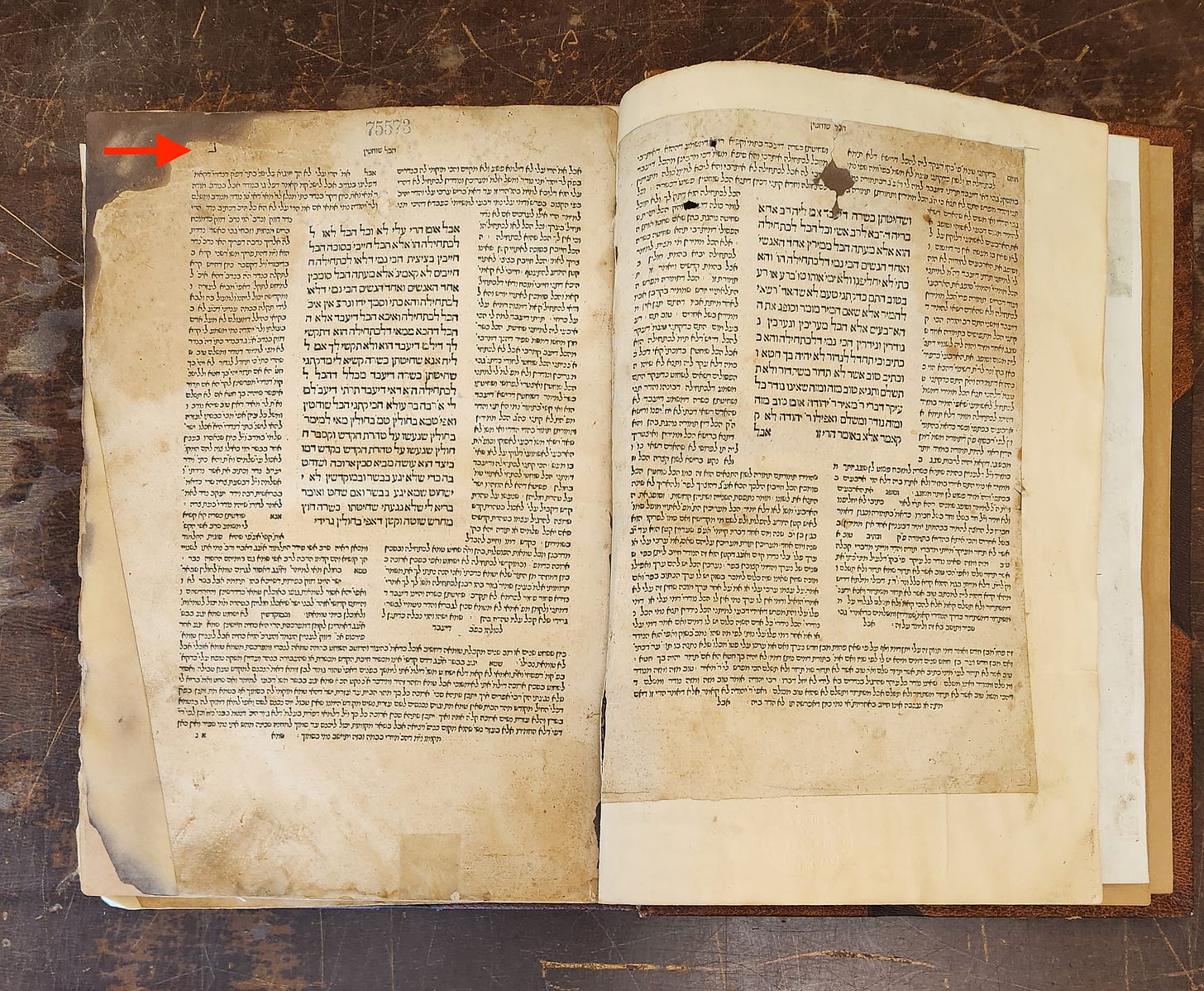

From the time the Talmud was written (around 500 C.E.) until the invention of the printing press in Europe in the 1460s, those who studied Gemara from a written text did so from hand-written manuscripts like the one featured below.

Ms.1180, meseches Shekalim, date unknown,

There is some evidence however that at least during the Geonic period (approximately 500-1000 C.E.) Gemara was largely studied ba’al peh (by heart) despite the fact that written texts existed, see Meiri in his introduction to Avos.

As one might imagine, the production of hand-written Talmudic manuscripts was both time consuming and expensive. As such, during the Medieval period Talmudic manuscripts were not widely available to the general public.

Thus, the philanthropy of the 11th century Spanish Rishon Rabbi Shmuel ha-Nagid (also known as Samuel ibn Naghrela) bears mentioning. This wealthy vizier to the Muslim king of Granada generously sponsored the production of Talmudic manuscripts (and Geonic writings) to scholars in need. At a time when Talmudic manuscripts were simply not affordable to the average Jew, Rabbi Shmuel ha-Nagid’s noble deeds greatly enhanced Talmudic scholarship in many countries beyond his native Spain.

We can also better understand the devastating effect of the ‘Burning of the Talmud’, during which more than 1,000 Talmudic and rabbinic manuscripts were incinerated in Paris in 1242.

Since Talmudic manuscripts weren’t mass produced during the Medieval period there wasn’t any centralized entity charged with their publication. Without any formality in production there was no tzuras ha-daf (standardized page layout). Rather, each individual would have his Talmudic manuscripts written in the size he preferred and with the commentaries that he desired.

The Advent of Printing and the Development of the Daf

The tzuras ha-daf with which we are familiar began to take shape at the turn of the 16th century as the printing press gained momentum (primarily in Italy) and Jewish and non-Jewish printers began printing the Talmud Bavli.

The Soncino Edition of the Talmud Bavli

Aside for perhaps some slightly earlier printings on the Iberian peninsula, the first to print (at least part of) the Talmud Bavli was the Soncino family in 1489.

Soncino Talmud, meseches Chullin, Soncino, Italy June 14 1489, CIN Library, RBR, AA Marx 62.

As can be seen in the picture above, the margins are completely empty with the exception of a page number that appears in the top left corner. However, the page number was not actually part of the printing but was added later, presumably by one of the owners.

Rashi and Tosfos appear on the two sides of the Talmudic text, thus giving the page the general tzuras ha-daf with which we are familiar. Aside from Rashi and Tosfos, the Soncino edition did not contain any additional mefarshim (commentaries).

The Bomberg Edition of the Talmud Bavli

The Daf changed dramatically when Daniel Bomberg printed his various editions of the Talmud Bavli between 1519-1549. Bomberg and his staff were the first to introduce pagination, in other words the concept of the Daf!

They also selected several additional commentaries to be printed at the end of the volume: Piskei Tosfos, Rambam’s Peirush Mishnayos (although for some reason the Rambam’s name is omitted), and Piskei ha-Rosh.

Bomberg Talmud, meseches Chullin, Venice, Italy 1519-1520,CIN Library, RBR 2043.

The Giustinianian Edition of the Talmud Bavli

Daniel Bomberg’s innovation of the Daf paved the way for his apprentice, Marco Antonia Giustiniani, to significantly enhance the study of the Talmud Bavli. In 1545, Giustiniani hired a Spanish refugee named Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz (author of Shiltei ha-Giborim on the Rif’s Sefer Halachos) to add important reference tools to the Daf.

These three works, which were printed on the margins of the page, are indispensable to the student of the Talmud:

1. Torah Ohr references the perek (and sometimes pasuk) in Tanach which the Gemara quotes. This enables the student to quickly locate the full pasuk, understand the context, and look up other relevant commentaries. In newer editions Torah Ohr has been upgraded to include a citation of the entire pasuk which is being referenced.

2. Mesores ha-Shas cross-references other Talmudic sources mentioned in the Gemara, Rashi, and Tosfos. In the 18th century, Rabbi Yeshayah Pik Berlin (1719-1799) expanded and upgraded the Mesores ha-Shas. The value of this work is immeasurable when considering the fact that many Talmudic sugyos (subjects) are scattered throughout the vast ‘Sea of the Talmud’. With relative ease, we can flip through a two or three hundred page mesechta and find the precise words within minutes.

It bears mentioning however that Mesores ha-Shas was not originally created by Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz. The original work, titled Mesores ha-Talmud (the censors changed it to Shas because the word Talmud was illegal) predated the printing press, and since the Daf didn’t yet exist, only the perek was referenced. Once Bomberg invented the Daf Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz added the page number to the reference. Interestingly, remnants of the original work can still be seen today, for example, the very first reference in the Talmud reads :מגילה פרק ב׳ דף כ. The perek (chapter) is still included even though the exact Daf is referenced.

3. Ein Mishpat references the halachic works relevant to a specific passage of the Talmud. In its original form, Ein Mishpat referenced the primary halachic codices of its day: Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, Semag, and Tur. [Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz’s Ein Mishpat predated Rabbi Yosef Karo’s Shulchan Aruch which was first printed in 1565. Subsequently, references to the Shulchan Aruch were added to Ein Mishpat.] This work is exceedingly important for one who is seeking to understand how the codifiers (such as the Rambam, Tur, and Shulchan Aruch) understood the halachic conclusions of the Talmud.

A somewhat ambiguous feature of Ein Mishpat is Ner Mitzvah which Rabbi Yehoshua Boaz intended to be his own commentary on the mitzvos. The commentary never came to fruition but the letters that referenced this work remained on the page. These letters were originally inserted in the margin between the text of the Talmud and Tosfos but were later placed next to the letters of Ein Mishpat. This is why one finds random letters in the Ein Mishpat that don’t reference anything.

Giustinianian Talmud, meseches Chullin, Venice, Italy 1546, CIN Library, RBR B 2047.

Images courtesy of the Klau Library, Cincinnati, HUC-JIR

What prompted Daniel Bomberg, a Christian from Antwerp, to engage in printing the Talmud?

There were likely several contributing factors and Marvin J. Heller shares one of them.

While in Venice attending to family business, Daniel Bomberg met Felice da Prato, an apostate who had become an Augustinian friar. It was Felice da Prato who is credited with convincing Bomberg to print Hebrew books.

If you're aware of other contributing factors, feel free to share them here.