Chacham Bashi of the Ottoman Empire

The Life and Works of the Romaniyot Torah Leader, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi

Enjoying these posts?? Help us spread the word!

Share Sheim HaGedolim Substack with your friends and family.

Rabbi Eliyahu ben Avraham Mizrachi, prominently known as ‘The Mizrachi’, is sometimes referred to by the Hebrew acronym רא״ם. [He should not be confused with the 13th century French Tosafist - Rabbi Eliezer of Metz who is sometimes referred to by the same acronym.]

Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi is widely known for his elucidative work on Rashi’s commentary on Chumash; however, perhaps less well-known is the important role he played as leader of the Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire prior to, during, and after it absorbed thousands of Spanish and Portuguese Jewish refugees at the turn of the 16th century.

Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi was born approximately 1455 in Constantinople (Istanbul) when Turkey was not yet dominated by Sephardic Jews. At the time, Constantinople (or קושטא in Hebrew) was a Romaniyot community, meaning its members were neither Sephardic or Ashkenazic. Jews originally settled in Turkey and Greece more than 2,000 years ago but have called themselves Romaniyot Jews since 324 C.E. when Constantine the Great moved the capital of Rome from the city of Rome to Constantinople thus absorbing these Jewish communities into his empire.

In his youth, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi studied under Rabbi Eliyahu Halevi the Elder in Constantinople and subsequently in the yeshiva of Rabbi Yehudah Mintz (1405-1508) in Padua, Italy.

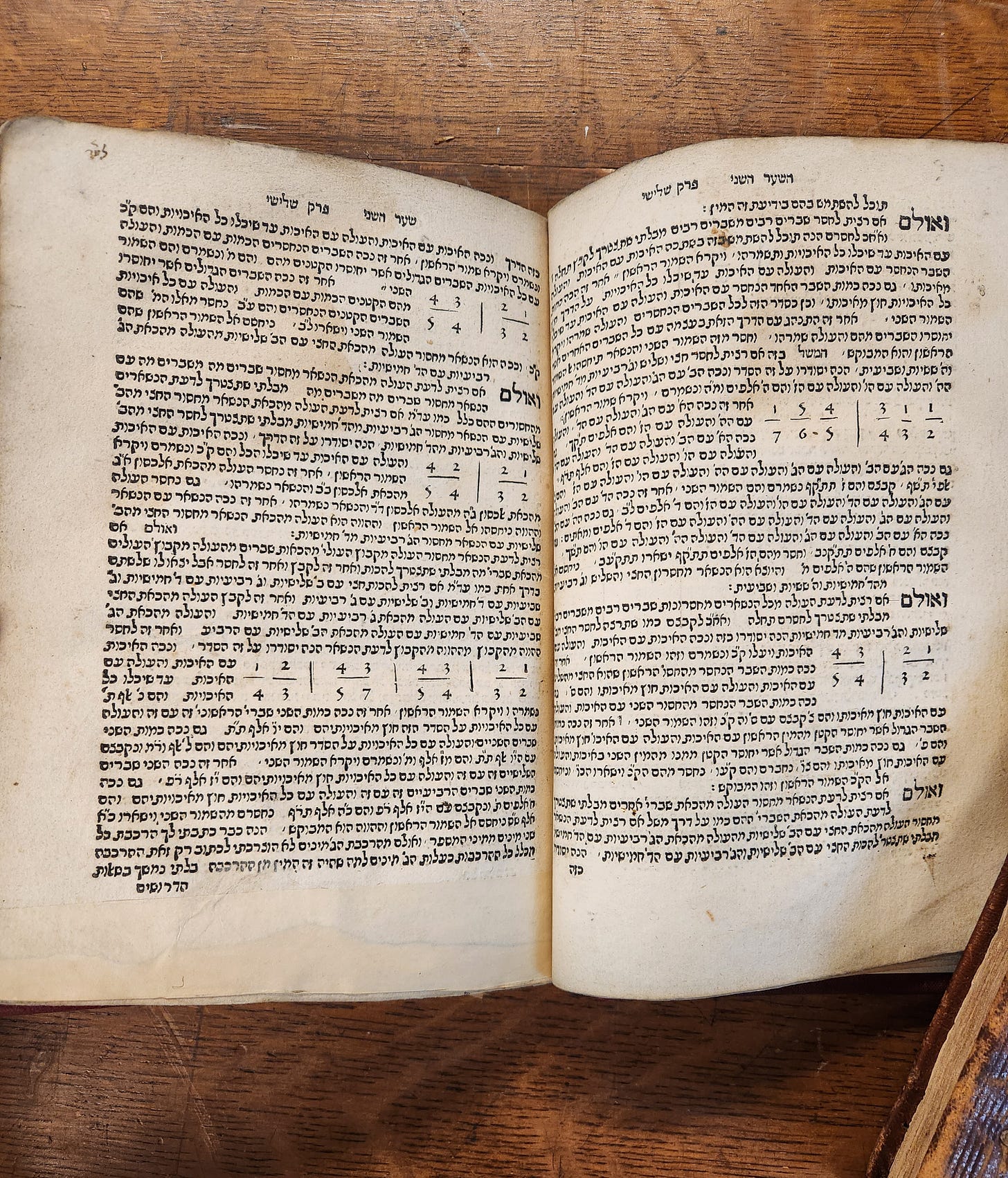

Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi began teaching at a young age and quickly became recognized as a remarkable Talmudic scholar. As Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi attests in a letter (responsum #56), in addition to teaching his students Gemara he taught them the sciences which they desired to learn. Among these subjects were mathematics and astronomy, fields which Rabbi Mizrachi occupied himself with on a consistent basis. In fact, in a responsum (#5) he mentions a commentary which he is in the process of writing on Ptolemy’s mathematical and astronomical treatise titled Almagest. Interestingly, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi viewed his devotion and commitment to the study of mathematics and astronomy as a fulfillment of the following Talmudic statement (Shabbos, 75a):

אָמַר רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: מִנַּיִן שֶׁמִּצְוָה עַל הָאָדָם לְחַשֵּׁב תְּקוּפוֹת וּמַזָּלוֹת — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם וַעֲשִׂיתֶם כִּי הִיא חׇכְמַתְכֶם וּבִינַתְכֶם״

Upon the death of Rabbi Moshe Capsali in 1495, Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi was selected to serve as the Chacham Bashi (chief rabbi) of the Ottoman Empire, a position of immense power and influence. By appointment of the sultan, the Chacham Bashi was granted the rights to govern the Ottoman Jews in accordance with Jewish law. Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi held this position for thirty years until his death in 1525. [So great was the power given to the Chacham Bashi, that other rabbinic judges were afraid to dispute his rulings. This led to a bitter controversy between the prior Chacham Bashi, Rabbi Moshe Capsali and Rabbi Yosef Colon (Maharik) of Italy, see Koreh Hadoros, pp. 105-106 in the Ahavat Shalom edition].

Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi’s appointment as Chacham Bashi of the Ottoman Jews (in 1495) coincided with a tumultuous time for the Jews of Spain and Portugal. Rabbi Mizrachi records that he took leave of his yeshiva for a full year during which he traveled from community to community collecting funds for the Spanish and Portuguese refugees.

One of the great controversies which Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi dealt with was the status of the Karite Jews and specifically whether it is permissible to teach them Torah. In a lengthy responsum (#57), Rabbi Mizrachi takes issue with a cherem issued by the leaders of the community prohibiting anyone from teaching the Karites Torah.

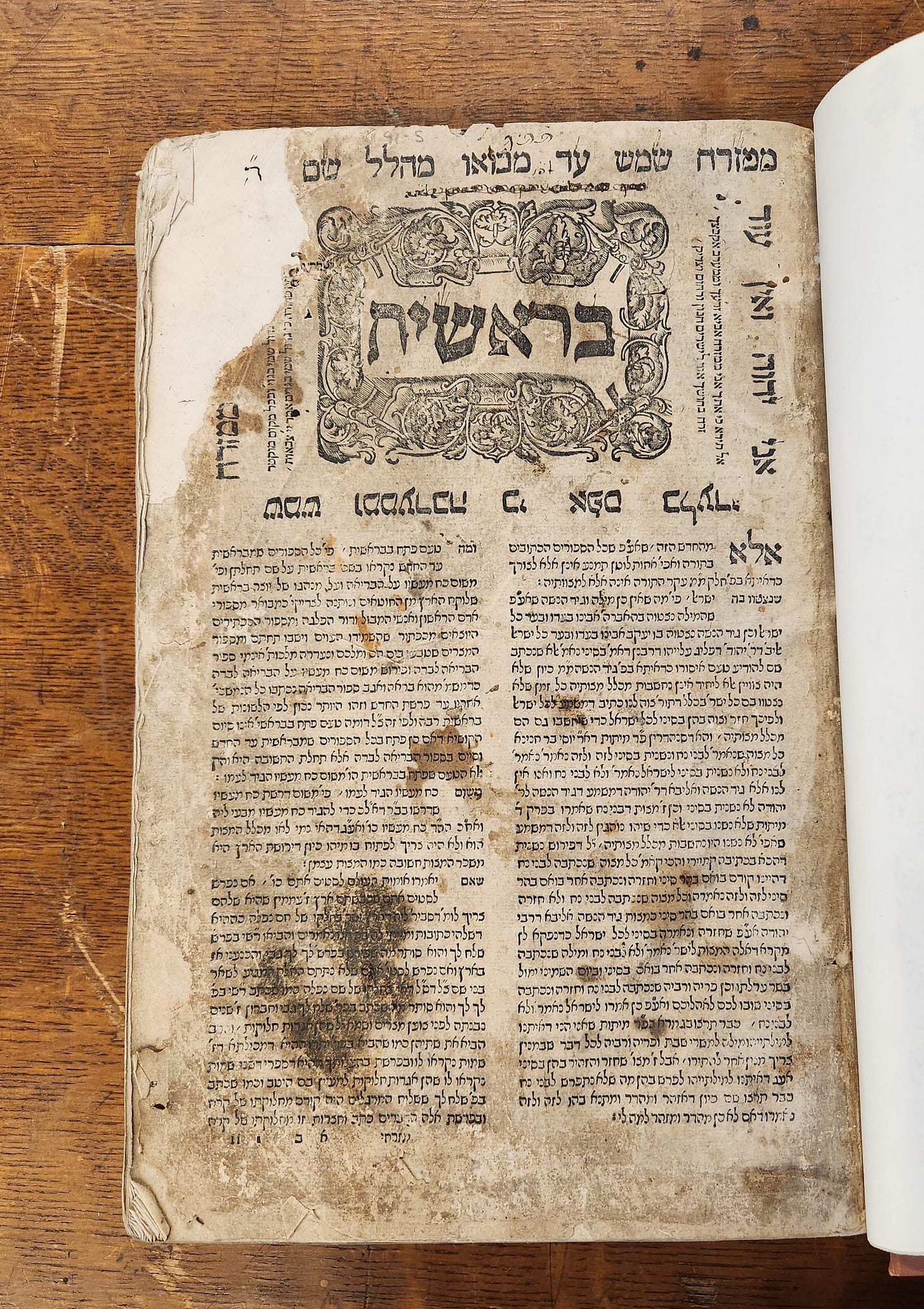

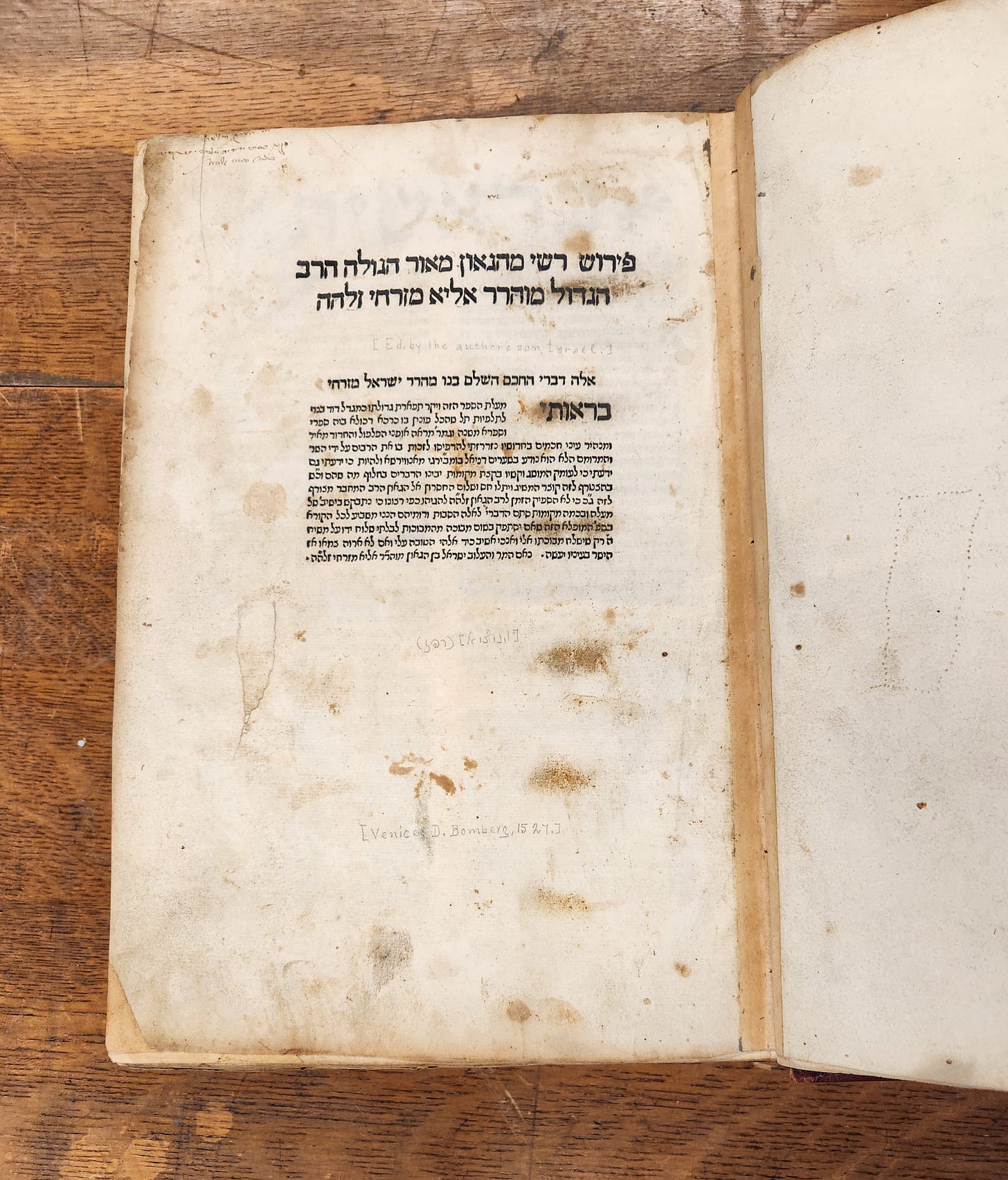

Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi’s most prominent work is undoubtably his Mizrachi (pictured below). In this super commentary on Rashi’s commentary on the Chumash he seeks to identify Rashi’s Talmudic and Midrashic sources and attempts to elucidate difficult passages. In doing so, Rabbi Mizrachi resolves many of the commentators questions on Rashi, in particular those of the Ramban. In a responsum (#5) he describes his overwhelmingly busy schedule and the time he devoted to writing this commentary:

“After ma’ariv a small group of students arrive and I teach them the Hilchos HaRif with the commentary of the Ran for nearly two hours. Afterwards, I sit down and write an exceedingly organized and intricate commentary on Rashi”.

So central was the Mizrachi to the study of Rashi that several abridged versions of the sefer were published over the centuries. Furthermore, although the Maharal of Prague often strongly disagrees with the Mizrachi, the fact that he cites the Mizrachi’s comments on nearly every page of his Gur Aryeh suggests that he viewed the Mizrachi as a foundational work for one seeking to understand Rashi.

A second work is Tosfei Semag, in which Rabbi Mizrachi expounds upon the laws of the Sefer Mitzvos Gadol (Semag) written by the French Tosafist Rabbi Moshe of Coucy.

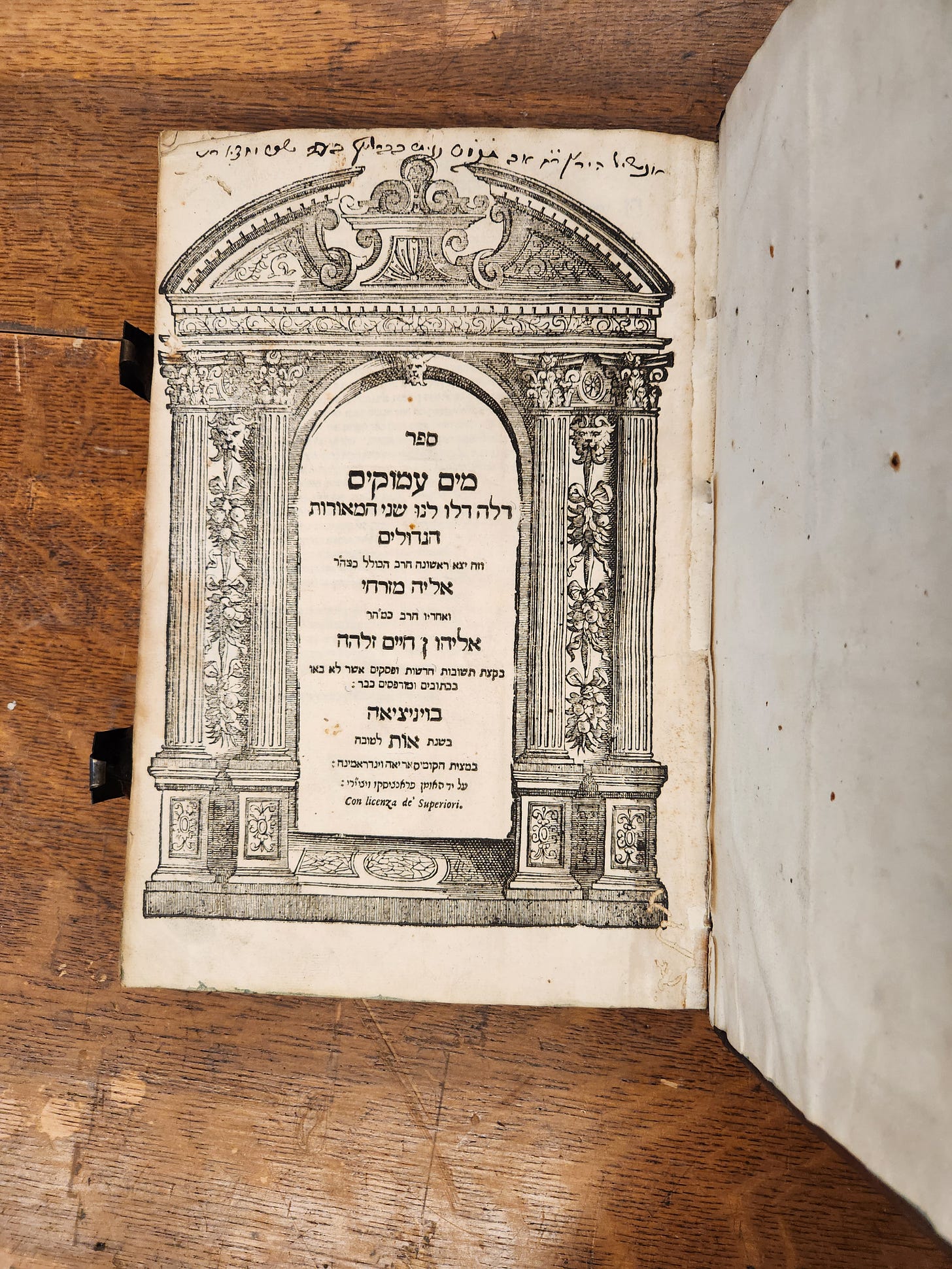

Other published works include Rabbi Eliyahu Mizrachi’s one hundred and thirty nine responsa (published in two volumes, one volume titled Mayim Amukim is pictured below) and a work on mathematics titled Meleches Hamispar (pictured below). His commentary on Ptolemy’s Almagest is not extant.

Mizrachi, Bomberg edition (Venice, 1545)

Mizrachi, Adelkind edition (Venice, 1527)

Responsa, Mayim Amukim (Venice, 1647)

Meleches Hamispar, first edition (Constantinople, 1533)

Images courtesy of the Klau Library, Cincinnati, HUC-JIR.

Thank you for your write-up on this important Gadol. Also worthy of mention is that of all the Chazal, the Ge’onim, Rishonim and Acharonim, only one was a Romaniote: the Re’em. He was a a guiding light, a posek, and a wonderful role model. May his memory be a blessing.