חד גדיא: One Little Goat

The History and Importance of the Classic Pesach Seder Song 'Chad Gadyah'

Ancient Jewish texts originating from the Mishnaic (Tannaic) period have expanded greatly over the centuries to include a liturgical component known in Hebrew as piyutim. A classic example is the siddur. At its core are the tefillos (prayers) composed by the Anshei Keneses Hagedolah (the Men of the Great Assembly). Over the centuries numerous piyutim have been added to the siddur, with different Jewish communities reciting their own unique liturgy. Likewise, the Pesach Haggadah is a collection of Tannaic teachings, elucidations, and interpretations, which, over time has been interspersed with piyutim.

One example is the well-known song Chad Gadyah.

According to a manuscript from 1406, the popular seder song Chad Gadyah originated from the Beis Midrash of the renowned 12th century German Kabbalist Rabbi Elazar of Worms, commonly known as the Rokeach (see The Rishonim, pp. 88-92) and might be linked to a narrative between Avraham and Nimrod mentioned in a Midrash (Midrash Rabbah, Noach 38[39]:13).

While Chad Gadyah (with its hilarious and entertaining motions and sounds) is a cherished part of the Pesach seder for children and adults alike, in truth this piyut has a deeper dimension which deserves some attention.

A fascinating 18th century responsum illustrates this very point. The Chida (Chaim Sha’al, vol. 1, #28) received a question about somebody who ridiculed the song Chad Gadyah among a group of friends. An enraged colleague stood up and pronounced a cherem (excommunicative ban) on him. The questioner asked the Chida if the cherem is effective and if such a response was indeed appropriate?

The Chida replied that since all the great rabbis of Poland and Germany and their kehillos (communities) have recited Chad Gadyah for hundreds of years, one who degrades such a piyut has essentially mocked these great rabbinic leaders and is deserving of excommunication. The Chida relates two points to support his view about the importance of piyutim: 1) it is well known that which the Ari z”l said about the greatness of the German piyutim which are based upon profound Kabbalistic ideas, 2) it has been said in the name of Rabbi Elazar of Worms (the Rokeach) that both the precise wording and concepts of piyutim were part of an oral transmission over the generations.

The Chida continues and informs the questioner that there are numerous commentaries on Chad Gadyah some of which have been published, others which remain in manuscript form. He writes:

עוד שמעתי ממגידי אמת שגאון אחד מופלא בדורו עשה למעלה מעשרה פירושים [על חד גדיא] בפרד״ס, פירושים נחמדים ומתוקים

I have also heard from ‘tellers of truth’ that a brilliant man, preeminent in his generation, composed more than ten commentaries [on Chad Gadyah] using [the four dimensions] of Pardes, commentaries that are precious and sweet.

As an aside, here’s a fascinating Pesach trivia question: Did Rabbeinu Tam and his brother the Rashbam steal the Afikomen from their grandfather, Rashi?

The answer is most probably, no! The Talmud in Pesachim (109a) teaches that one should ‘grab the matzos’ in order that the children don’t fall asleep. According to Rashi, the phrase ‘grab the matzos’ means to either lift up the seder plate or start the seder right away, (see Rashbam for an additional explanation). However, the Rambam understands this phrase in its most literal sense, that the matzos should be snatched away from the leader of the seder. Rabbi Yakov Reischer (ca. 1660-1733), in his Chok Yakov, O.C. 472:2, posits that the Rambam’s interpretation is the source for the prevalent custom of allowing the children to steal the Afikomen. Evidently, this custom which originated in the lands that followed the Rambam spread to Ashkenazic countries as well.

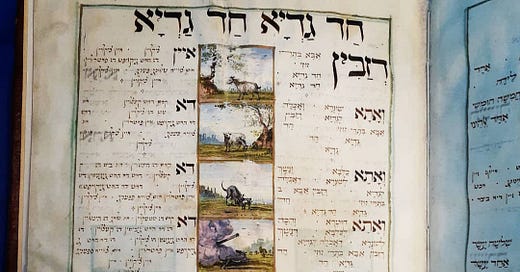

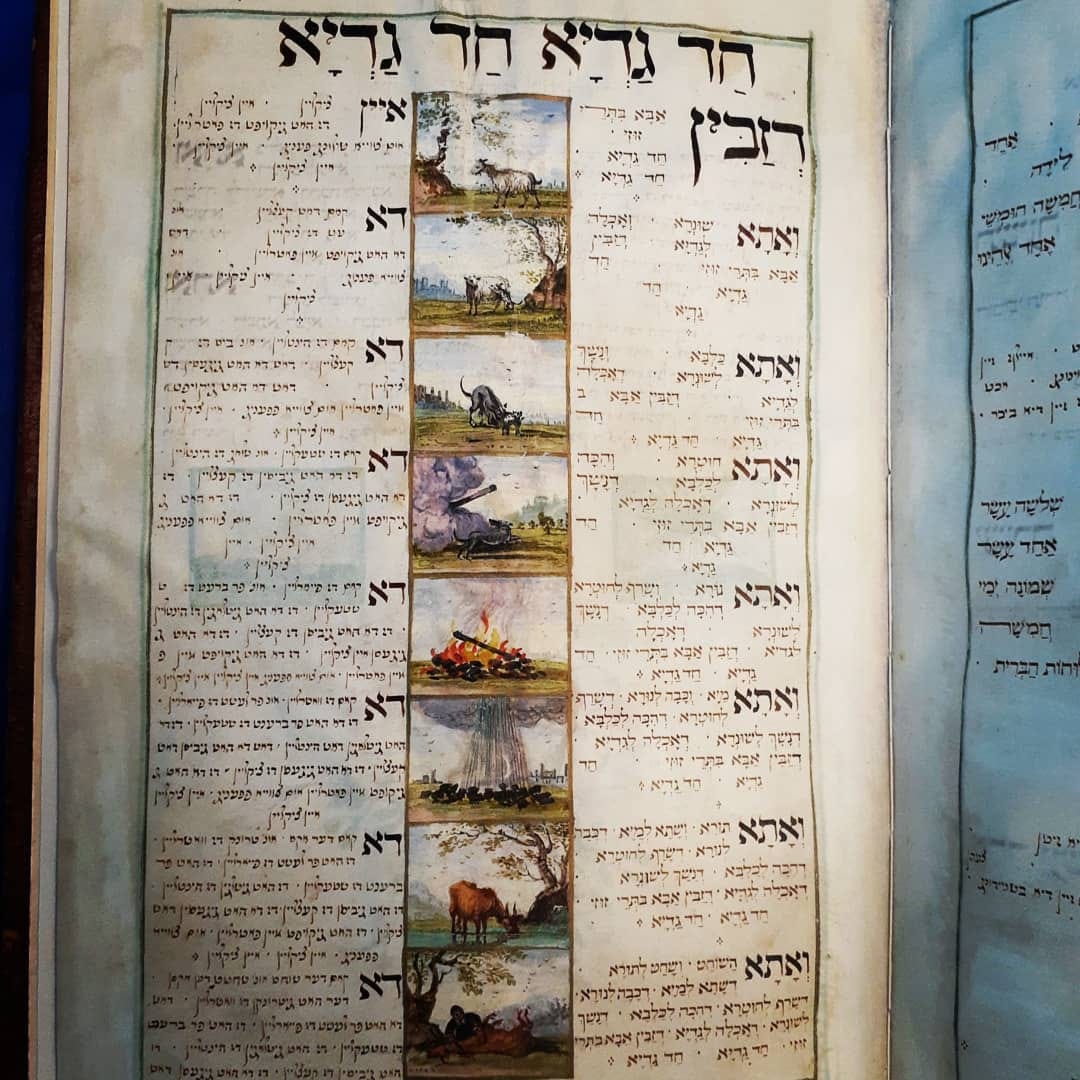

A Haggadah from Moravia (1716)

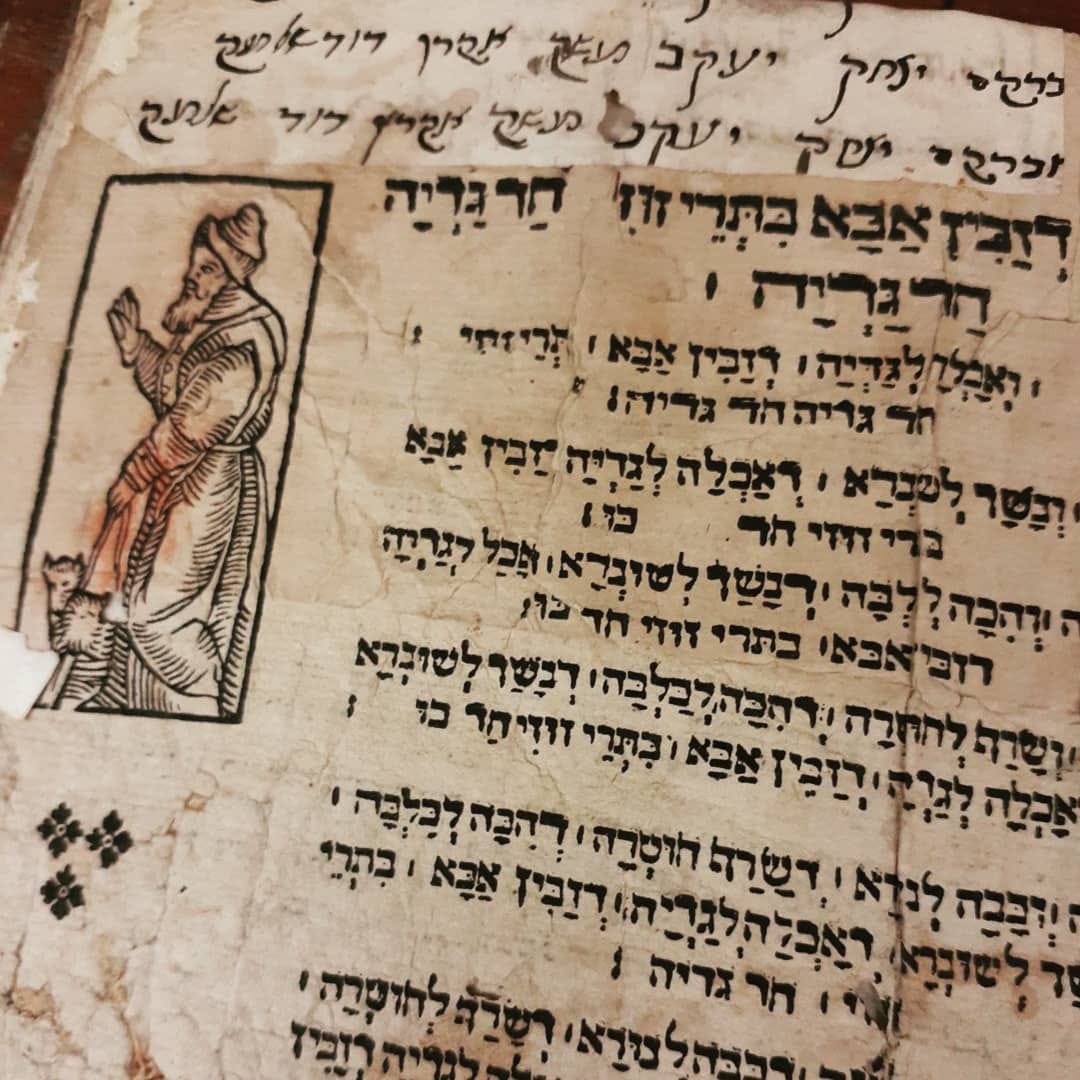

A Haggadah from Prague (1590)

Images courtesy of the Klau Library, Cincinnati, HUC-JIR.

I'd like to know more about this 1406 manuscript that attributes Ḥad Gadya to Rabbi Elazar of Worms. That's fascinating. Could you please provide a reference to the manuscript or to the secondary source from which this information was drawn? (Was this information found in The Rishonim, pp. 88-92, or is this reference provided for learning more about Elazar of Worms in general?)