As Pesach approaches, thoughts of galus (exile) and geulah (redemption) are certainly on our minds. Just as our forefathers in Egypt experienced a miraculous redemption from a bitter slavery, Jews in every generation experience the cycle of galus and geulah on personal, community, and national levels.

The tumultuous, yet extraordinarily productive life of Don Yitzchak Abarbanel (known simply as ‘the Abarbanel’) personifies this cycle of galus and geulah. As will be outlined briefly below, the Abarbanel experienced periods of intense and life-threatening galus followed by periods of glorious and prosperous geulah.

Born in Lisbon, Portugal in 1437, the Abarbanel rose to power in the court of King Alfonso. After a number of years of prosperity, he was tragically ousted by jealous colleagues. His next destination was Spain where he again rose to power, this time in the court of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, the notorious monarchs of the newly united kingdoms of Aragon and Castile. Ultimately his attempt to save the Jews of Spain was unsuccessful, and the Abarbanel led a portion of his expelled brethren east to Italy in the summer of 1492. The Abarbanel settled in Naples only to be forced to flee several years later when the French armies invaded and captured the city. After seeking refuge on the islands of Sicily and Corfu, the Abarbanel eventually returned to Italy and settled in costal town of Monopoli on the Adriatic Sea.

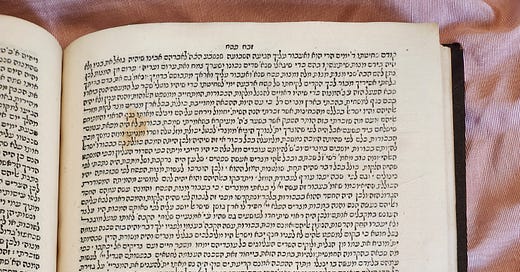

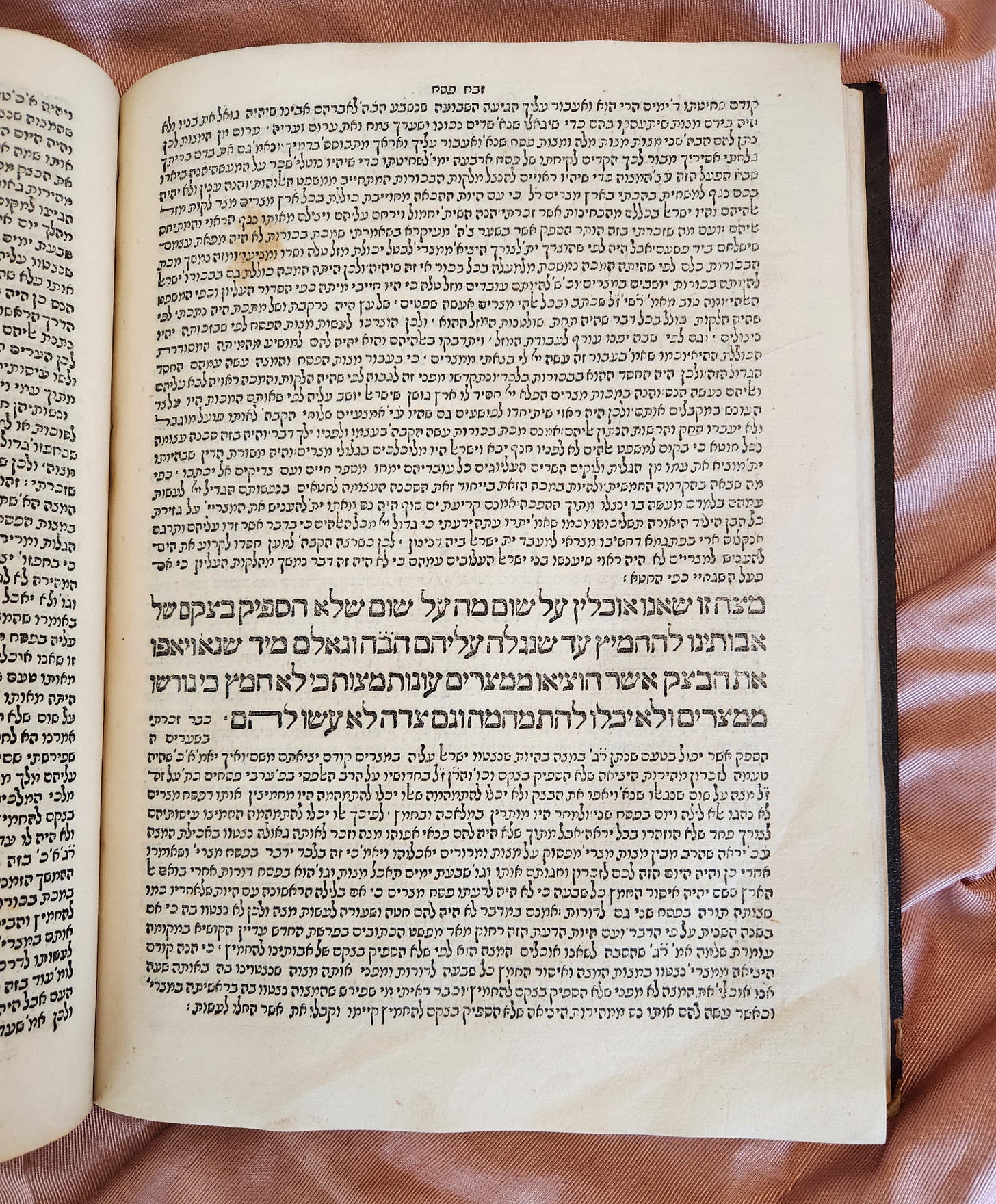

Despite tremendous physical and emotional suffering, the Abarbanel produced a remarkable array of sefarim. Among the Abarbanel’s many works is his classic commentary on the haggadah titled Zevach Pesach. This work was completed on erev Pesach 1496 in Monopoli and was first printed in Constantinople in 1505, several years before the author’s death. Zevach Pesach was printed by the Nachmias brothers (Shmuel and David) along with two of the Abarbanel’s other works, Nachlas Avos and Rosh Amanah.

[As an aside, why would the Abarbanel, who was living in southern Italy at the time, have his works printed in Constantinople instead of in Italy? Perhaps the following three factors played a role: finances - it may likely have been more economical to print in Constantinople, marketing - since many of the exiled Spanish Jews ended up in the Ottoman Empire, his works would have been more popular there, and connection to the publisher - the Nachmias brothers were connected to the Abarbanel in Spain. A special thank you to Avigaille Katz and Yoram Bitton for this information.]

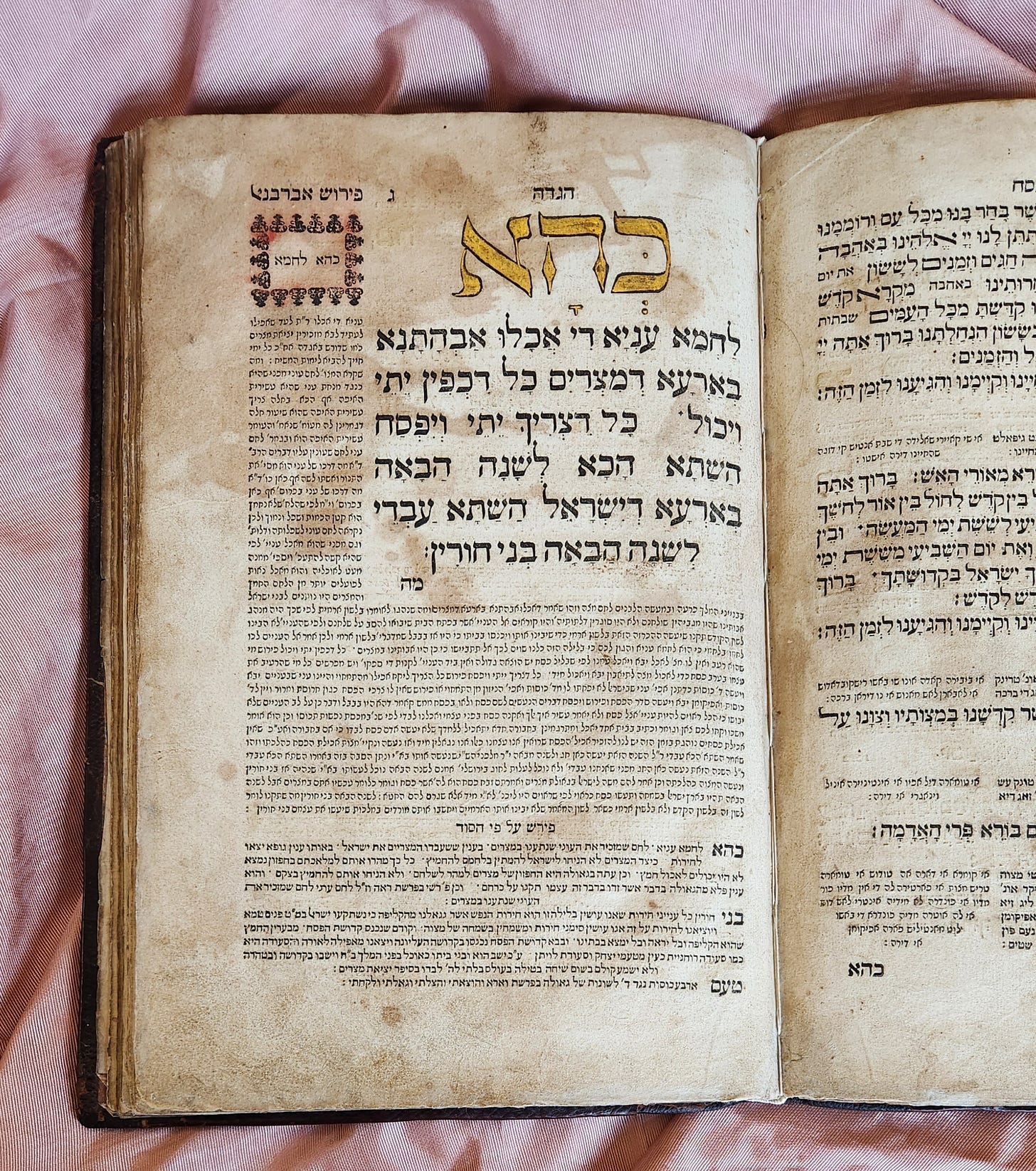

The first edition of Zevach Pesach is featured below:

The Abarbanel’s Zevach Pesach was so popular that two abridged versions were produced in the 17th century. One, written by Rabbi Yakov (ben Elyakim) Helprin, was published in Lublin in 1605, the other, titled Tzle Aish, was produced by Rabbi Yehuda Aryeh Modena in 1639. These abridged versions condensed the Abarbanel’s lengthy commentary making it more accessible to the public. The former version (produced by Rabbi Helprin) earned the haskamos of the great Torah leaders of eastern Europe.

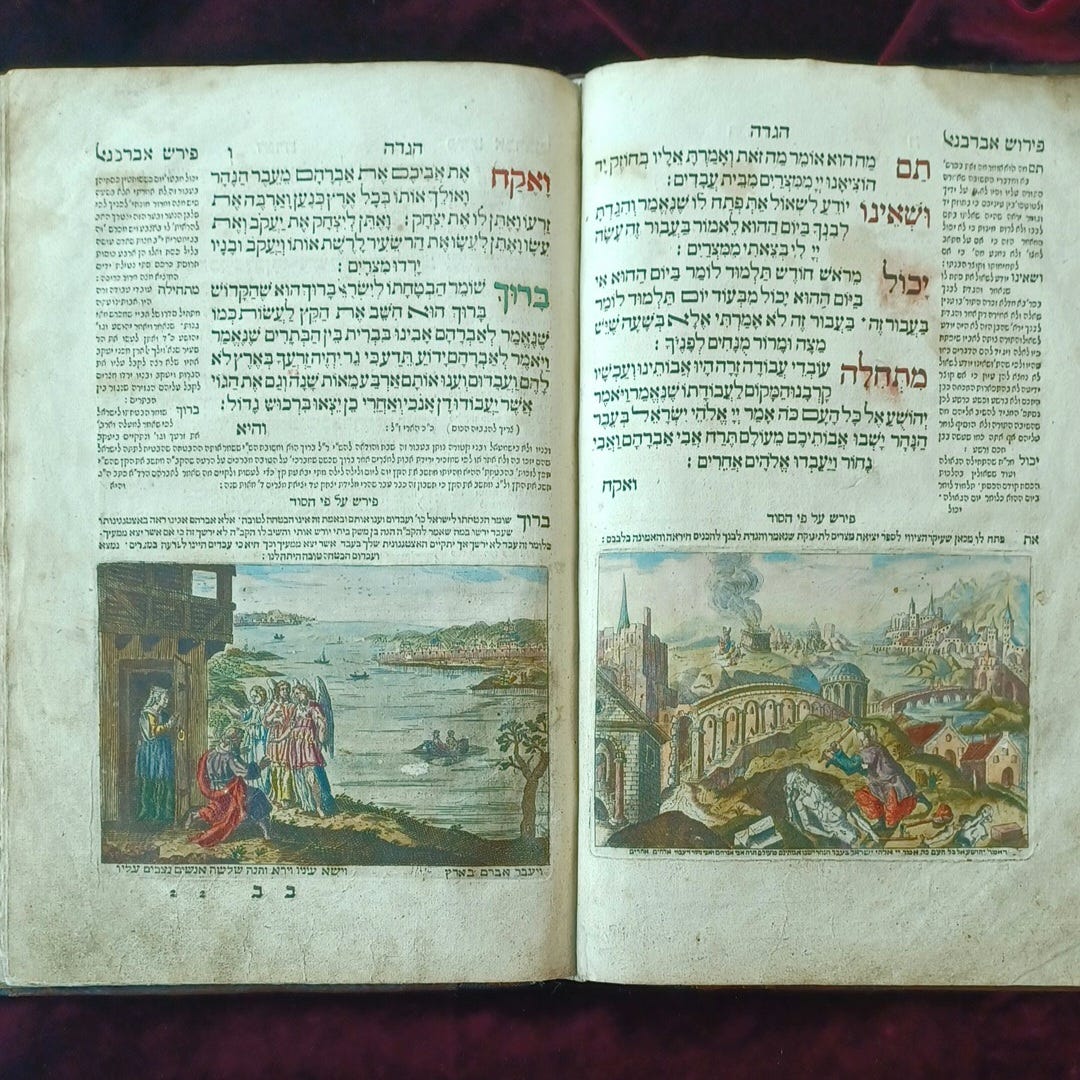

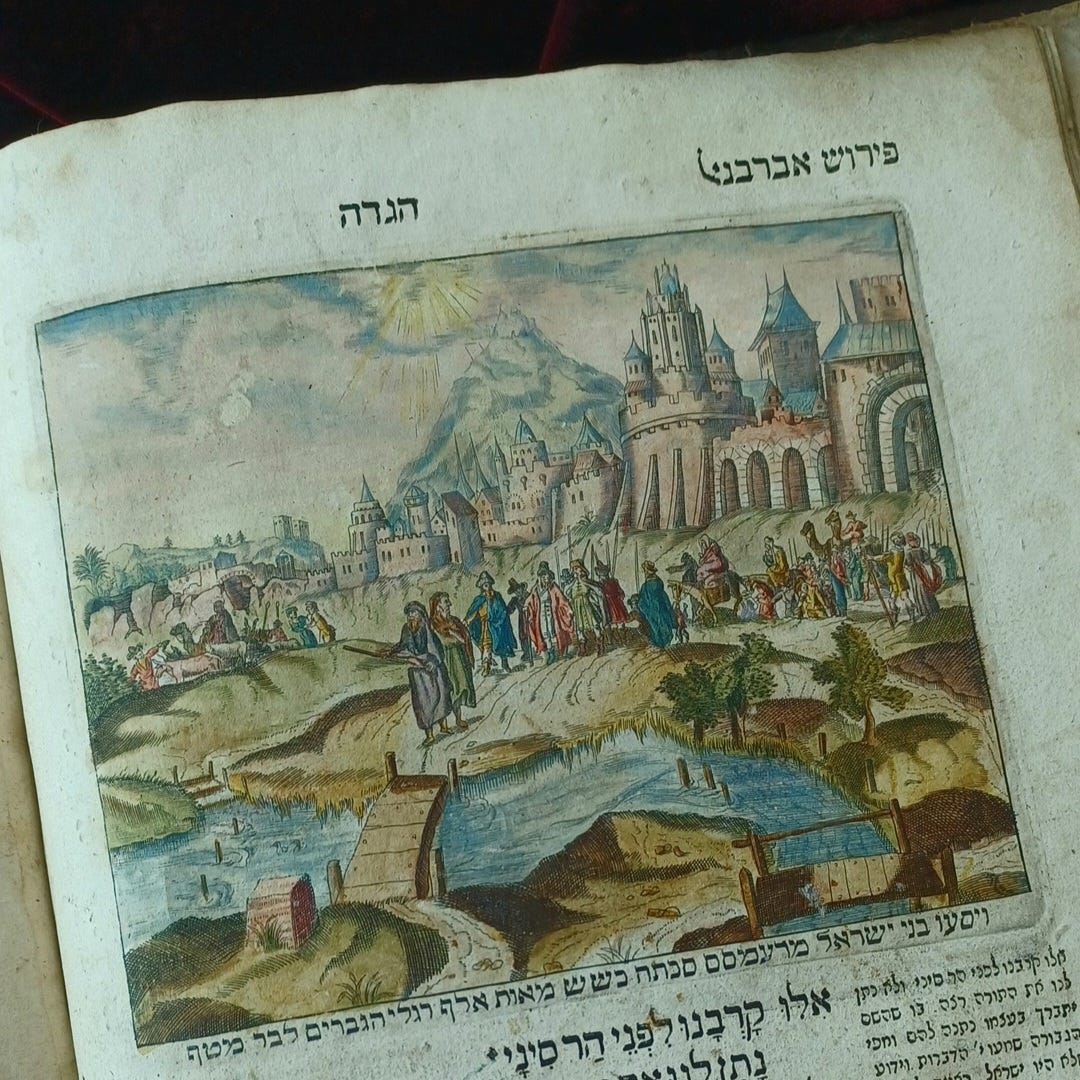

Many printers selected Zevach Pesach as the commentary to elucidate the text of the haggadah, another indication of its popularity. One such example is the beautiful Amsterdam haggadah (1695) featured below:

Images courtesy of the Klau Library, Cincinnati, HUC-JIR

There is a lot of discussion and debate about the origin of his name and the correct pronunciation. I went with Abarbanel because I feel that people are more familiar with this pronunciation even though it may be incorrect. Thank you for you comment.

I believe his name is pronounced Abravenel.