The Contents of the Collection

Ever since his late teens, Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim possessed a passion for collecting sefarim (Hebrew books). By the time of his passing in 1736, his collection contained an outstanding 4,220 printed books and 780 manuscripts in Hebrew, Yiddish, and Aramaic! Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim meticulously catalogued the details of each purchase he made including the price, the seller’s name, and other pertinent information.

Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim’s Methods of Acquisition

Buying books in the 17th and 18th centuries was very different than buying them today. Jewish book stores as we know them today hardly existed in 17th century Europe; instead, most new books were sold directly by printers, publishing houses, or private vendors. Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim built his collection through a number of different means:

Occasionally Rabbi Oppenheim acquired new sefarim directly from printers and publishers.

Rabbi Oppenheim frequented the annual trade fairs in Frankfurt and Leipzig where hundreds of vendors sold sefarim.

The bulk of Rabbi Oppenheim’s purchases were second-hand, either by purchasing individual volumes or entire collections. In his early years, Rabbi Oppenheim purchased sefarim from local sellers in Worms, but over the decades he developed contacts across Europe and the Middle East.

Rabbi Oppenheim also received sefarim in the form of gifts. In 1681, upon his marriage to Genendel, daughter of Leffmann Behrens Cohen, he received several sefarim from well-to-do relatives and friends. Later in life, as a respected rabbi, Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim received many sefarim, specifically those for which he wrote haskamos.

Printing the Rashbam’s Commentary

In the 1680s Rabbi Oppenheim chanced upon a large pile of manuscripts in the genizah of a shul in Worms. Among other literary treasures, Rabbi Oppenheim discovered the Rashbam’s commentary on the Chumash which he printed in 1705. This was the first time the Rashbam’s 12th century commentary on the Chumash was published.

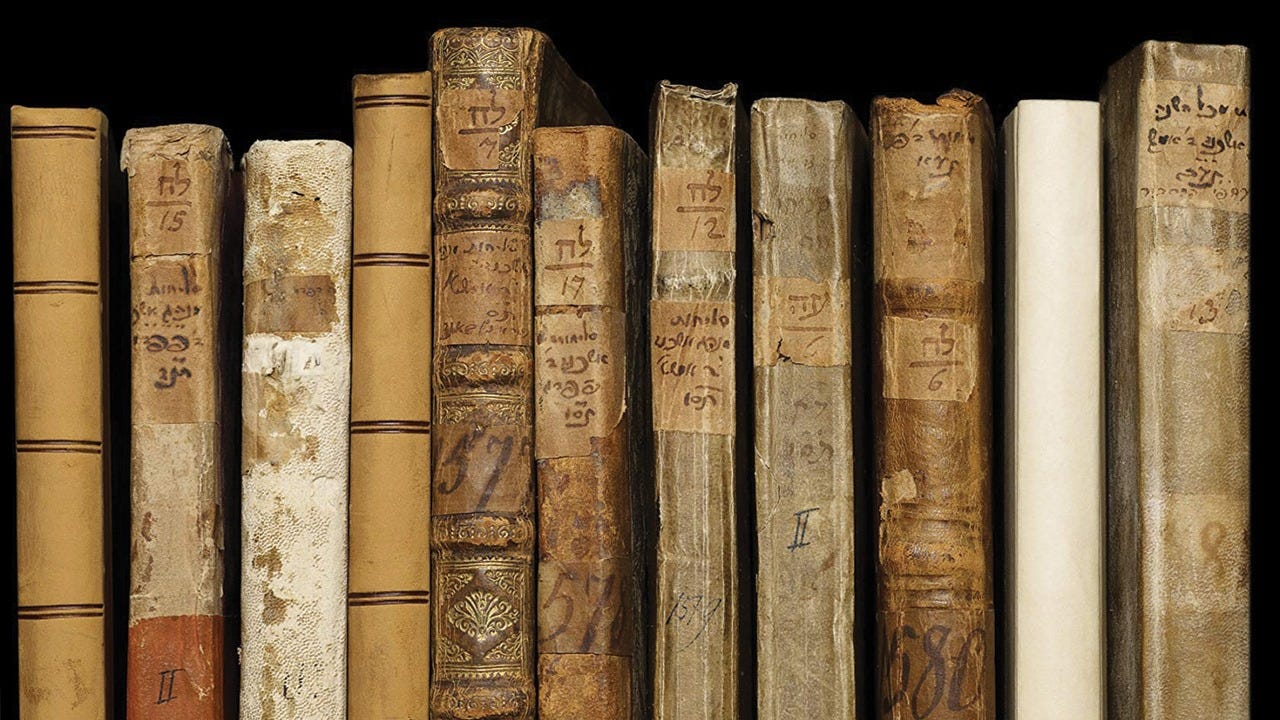

The Collection’s Journey through Western Europe

The majority of Rabbi Oppenheim’s library which had been divided between Worms and Hanover accompanied him to Nikolsburg in 1691. However, since laws prohibiting the ownership of certain types of Hebrew books were issued in Bohemia during this time period1, upon his move from Nikolsburg to Prague (in Bohemia) in 1703, Rabbi Oppenheim transferred his library to the estate of his father-in-law, Leffmann Behrens Cohen, in Hanover. By 1710, Rabbi Yosef Oppenheim had relocated to Hanover where he assumed responsibility for his father’s library. He and several others organized the library into 106 sections and numbered each volume.

For the last three decades of his life, Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim remained separated from his library. Although this certainly disappointed Rabbi Oppenheim, ultimately the ban against bringing Hebrew books into Bohemia saved his library from destruction because between 1704-1706 a large number of Hebrew books were confiscated and destroyed in Prague.

Catalogues, Evaluations, and Auctions

After Rabbi Dovid Oppenheim’s death in 1736, his library was inherited by his son, Rabbi Yosef Oppenheim who had been caring for the library ever since his move to Hanover in 1710. But Rabbi Yosef Oppenheim suddenly passed away three years later in the summer of 1739, and the collection was transferred to his daughter, Genendel, married to Rabbi Hirsch Oppenheim of Hildesheim. In Hildesheim, the collection was itemized and a catalogue was produced for the purpose of auctioning off the library.

However, the auction did not occur in Hildesheim and the library was transported yet again to Hamburg where it was acquired by Genendel and Hirsch’s daughter and son-in-law, Raizel and Isaac Baer Cohen. Under their ownership, in 1782 another catalogue was created to attract potential buyers. A few years earlier, in the late 1770s, Moses Mendelssohn estimated the collection’s value at 50,000-60,000 reichsthalers, however other evaluators claimed the collection was worth more than 15,000,000 reichsthalers.

Although some interest in buying the collection was shown by David Friedlander, Jeremiah Heinemann, and Rabbi Shlomo Yehudah Rappaport, by the turn of the 19th century the library was still up for sale.

In 1826 another catalogue, titled Kehillas Dovid, was prepared by Isaac Metz and the library was yet again put up for sale. It was determined that if no buyer came forth then an auction would be held on June 11, 1827. A series of drawn-out negotiations between the Bodleian Libraries of Oxford University and the Oppenheim family began in the winter of 1826 and culminated in May, 1829, with the purchase of the entire library (34 crates) for the bargain price of 9,000 thalers!

The contents of this remarkable collection can be viewed on Digital Bodleian: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/collections/oppenheim/

Following the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) the Hapsburg monarchs sought to eradicate heretical literary material from its kingdom. In 1669, the governors of Bohemia ordered the closure of two Jewish printing houses in Prague owned by the Back and Löbl families, and just a few months later, in January 1670, the local authorities confiscated several hundred volumes of the Talmud and more than 1,000 other Hebrew books. Although the printing houses were allowed to reopen in 1674, any Hebrew book that was prepared for publication had to be approved by the censorship committee headed by a group of Catholic bishops and professors. Violators were harshly punished as was the case with two Jews from Prague – Berel Back and Yisrael Kettwies, who printed a siddur without permission. Random searches were also conducted by local police as was the case in 1712 when forty-two families were subject to an investigation. In 1714 the tractates Sanhedrin and Chullin along with cartloads of Hebrew books were burned in the center of Prague.